With so much of the Lewis and Clark Expedition focused on the new and undocumented, it can be easy to forget that when they arrived at the mouth of the Columbia they were entering territory well explored. Not only was the region already on the maps, but it was also constantly visited by trade ships looking to make a fortune off the local sea otter and other furs. Thousands of furs were being acquired per ship in the Pacific Northwest, with a grand majority of ships coming from Boston or Great Britain.

Trade ships coming to the Pacific Northwest brought with them a myriad of items for the purpose of trade. Everything from copper sheeting to rice and molasses was seen as a potentially valid trade good. Every first nation in the Northwest, from the Aleuts and Kodiaks of the far north to the Tillamook and Umpqua of the southern portion, had their own unique culture and different value for each trade good. While copper was used in everything from daggers to masks, the musket market would prove equally valuable for a short period of time.

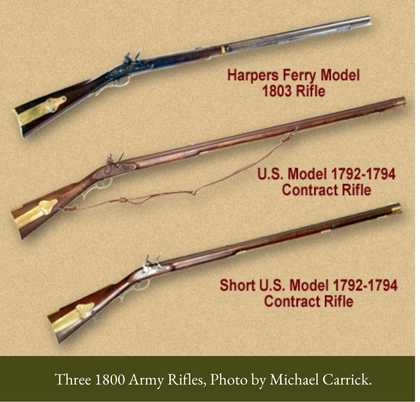

As the expedition members entered the Pacific Northwest, they saw multiple signs of the ongoing trade. A few miles below the Dalles along the Columbia, October 28, 1805, Clark writes about seeing a family with a “British musket.” These muskets were smaller than those carried by the expedition whose muskets rang in at .69 caliber while the trade guns were typically around .60 caliber.

The members all noted that the guns here on the coast looked to be older American and British models and were very often in states of disrepair. Although Captain Clark would state on January 15, 1806 that the locals “appear not to be long enough acquainted with firearms to understand the management of them” one need only be more familiar with the climate on the coast to see why guns did not last long.

“Some little rain all the last night with wind, before day the wind increased to a Storm from the S. S. E. and blew with violence throwing the water of the river with emence waves ut of its banks almost over whelming us with water, O! how horriable is the day— This Storm Continued all day with equal violence accompanied with rain, Several Indians about us, nothing killed the waves & brakers flew over our Camp, one Canoe Split by the Tosing of those waves— we are all Confined to our Camp and wet.” William Clark, 22 November 1805

With an average rainfall upwards of 80 inches a year, this moisture combined with saltwater and airborne salt, corrodes metal at a much faster rate than normal rain and humidity. The guns of old were simply not built to withstand this region and would rust and decay rapidly.

Despite the shortened lifespan of guns in the Northwest there were so many coming in from trade vessels that by the time of the expedition they had considerably dropped in value. William Sturgis, a merchant-historian of the era, provides very detailed notes and insights on the trade in the Pacific Northwest between the years of 1799 and 1802. In his accounts he starts in 1799 by writing that 1 musket would often fetch a price of 3 sea otter skins, and by the end of 1799 it was 5 skins for 1 musket. The price dropped back to 3 skins per musket in 1800, but one year later, 1801, we reach a point where native nations were refusing to buy and instead were trying to sell guns back to ships.

The final year of records, 1802, would see that the only guns to sell were “kings arms” or handsome fowling pieces which amounted to smoothbore guns that could shoot multiple small lead shot at once.

We don’t know if the gun trade was returning in full force during the expedition’s time on the coast, but based upon the account of November 5, 1805, by Private Joseph Whitehouse, we can assume it was still worth little as he remarks that the locals wanted to trade only elk skins for expedition muskets and nothing else. However, this offer is refused, Joseph writes, “we having not more Rifles than what we wanted.”

It’s important to note that many people living on the coast only had experience with muskets, as these were cheaper, easier, and faster to produce than their counterpart, the rifle.

William Clark would introduce a flintlock rifle to some however on December 10, 1805, when he displayed the accuracy of this technology by shooting the head off a duck at a 40-yard distance.

This prompted the onlookers to exclaim in chinook jargon: “ƛuš musket, wek kǝmtǝks musket, “[it is a] good musket, [I do] not understand [this] musket.” The rifling in the barrel greatly extends the accuracy of the gun compared to the smooth bored barrel of a musket.

During the expedition’s time at Fort Clatsop, the presence of guns would help fix another problem the Corps had; their lack of trade goods. As the local people did not have much access to replacement parts or the tools to repair their guns, offering these services in place of their usual trade goods became a successful venture in acquiring supplies.

Clark writes on December 31, 1805, that an individual had brought a musket to be repaired.

After flattening a screw and replacing the man’s flint, Clark was given a peck of wapato root. These services could easily have been offered by John Shields as well, their resident blacksmith and gunsmith, whose ingenuity the captains always praised, for further trade, similar to their previous winter at Fort Mandan.

Guns became part of the residents’ lives here on the coast as much as they were part of the daily lives of Americans and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. To the expedition, this would serve as a boon and a return to technology they were familiar with. For the fur traders who brought them here by ship, they would for a time have been a source of great profit. While these were on occasion used as weapons of war or for self-defense, both the expedition and native nations would find them to be valuable tools for survival on a day-to-day basis in securing food more easily. Five years after the expedition’s departure, the Tonquin, a ship owned by John Jacob Astor, would arrive at the mouth of the Columbia to usher in another new chapter in the history of the Pacific Northwest with bigger guns and other trade goods to match. The cycle of trade continued.