Women’s History Month Blog Post

Women’s History Month was created with the mission of celebrating women who revolutionized our world. This year, we’d like to share the stories of four women who influenced the Lewis and Clark Expedition and Pacific Northwest History.

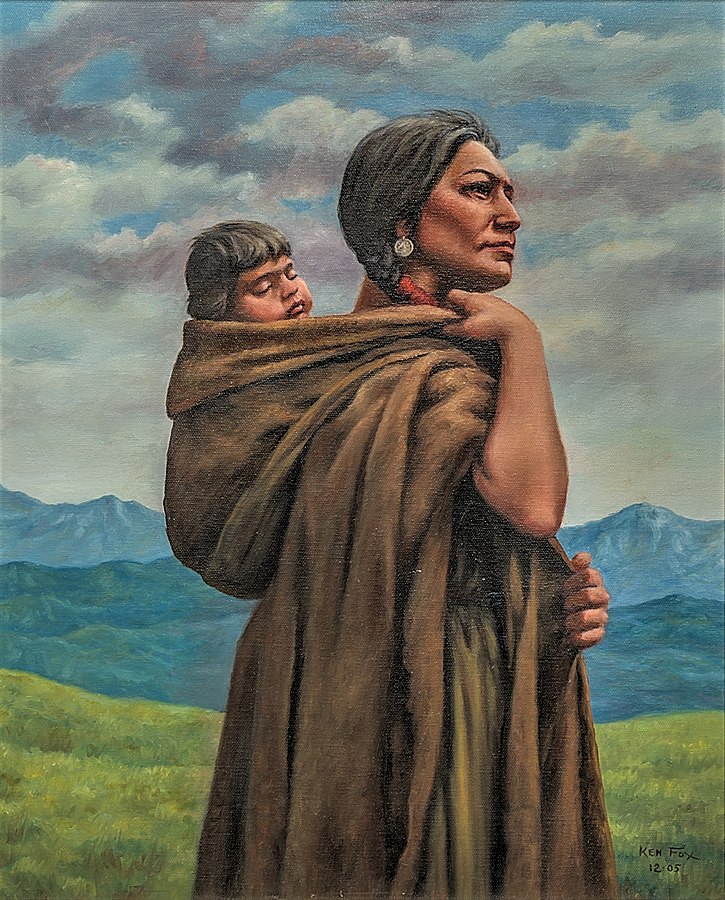

Sacagawea

Probably the best known on this list, Sacagawea, joined the Corps of Discovery as a guide and translator. Her knowledge was crucial to the Corps’ survival and success.

Sacagawea was a Lemhi Shoshone from today’s Idaho but had been captured during a raid by the Hidatsa when she was 11 or 12 years old. She was wed to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trader, while living at the Knife River Indian Villages.

She was 16 or 17 years at the time the Lewis and Clark Expedition arrived in North Dakota in late 1804. Charbonneau was hired by the Corps of Discovery as an interpreter, and Sacagawea was included due to her knowledge of the Shoshone language. The two officially joined the Expedition in November of 1804. Sacagawea was pregnant at the time and, while wintering with the Corps at Fort Mandan, gave birth to their son in February of 1805. She and their then two-month-old son, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, left with the Expedition when they continued their westward journey on April 6th, 1805.

Sacagawea was greatly respected by Lewis and Clark, and the two men value her insight and advice while crossing the continent. She was able to translate for the Corps, identify edible and medicinal plants, navigate difficult terrain. When the Expedition reached Lemhi Shoshone territory, her presence likely helped the Expedition obtain the horses they needed to cross the Rocky Mountains.

Sadly, Sacagawea would not be rewarded for her efforts upon the Expedition’s return. She was never paid or otherwise compensated for her invaluable work. She died young at Fort Manuel Lisa in 1812 from illness. William Clark became her son’s guardian after her death.

Julia Hancock

Though she is often overlooked, it’s possible Julia Hancock influenced William’s Clark’s decision to join the Corps of Discovery. Clark met Julia before heading out on his expedition to the Pacific Ocean, and was quick to marry her on his return.

According to the Hancock family, Clark initially met Julia in 1801 when she was 11 or 12 years old. She was riding horses with her cousin, Harriet Kennerly, when one of the horses became frightened and the young girls had difficulty returning home. It was then a 30-year-old William Clark happened by, helping escort the girls home.

Though the age difference between Clark and Julia is strange to us today, it was not uncommon for the time. Given her family history, Julia would have been highly sought-after as a spouse, and Clark likely had fierce competition for her hand. Julia’s father, Colonel George Hancock, was a wealthy Revolutionary War veteran. Clark expressed his interest in the young Julia, but Colonel Hancock did not give him permission to court his daughter at first. Some historians speculate Clark’s desire to prove himself worthy to Julia’s protective father may have inspired him to join the Corps of Discovery.

Along the trail, Clark named a tributary in Missouri “Judith River” after his future wife. When he returned from the Expedition in September of 1806, he wasted no time. He began courting Julia in 1807 and the two were wed a year later in March of 1808. By all accounts, Clark and Julia had a happy marriage.

We know very little about what Julia was like, save for the letters Clark wrote. His impassioned words of praise for his young wife indicate he held a deep affection for her, detailing her love of music and Shakespeare, her cooking and canning, and her multiple pregnancies.

By the age of 28, Julia had become a mother to five children: Meriwether Lewis Clark, William Preston Clark, Mary Margaret Clark, George Rogers Hancock Clark, and John Julius Clark. Tragically, Mary Margaret Clark and John Julius Clark did not survive to adulthood. Julia’s life was also cut short by an unknown illness. She passed away in 1820. Clark remarried a year later to Julia’s cousin, Harriet Kennerly, who he had met on the same fateful day as Julia.

Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks

It’s said that behind every great man is a great woman, and behind Meriwether Lewis was Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks. Lewis’ mother Lucy was a skilled naturalist with an expansive knowledge of herbal medicine. She was described as highly intelligent, bold, and sincere. She was described as “a devoted Christian and full of sympathy for all sickness and trouble.” According to family stories, she was as brave as she was compassionate. One family story claims Lucy once took a gun and drove off a group of drunken British soldiers from her home during the Revolutionary War.

Lucy was highly regarded as a local folk healer. She likely learned much of her craft from her father and used her talent with plants to treat patients. Lucy passed along her knowledge to her son, and during his upbringing encouraged young Lewis’ interest in plants and wildlife. On the Expedition, Lewis became the primary doctor, relying on what he had learned from his mother to keep himself and his crew healthy. Much of his abilities as a healer and a leader can be credited to his upbringing.

Lewis even saved himself thanks to his mother’s teachings. While traveling through what is now Montana in 1805, he fell ill with a fever. He was unable to eat or keep up with the rest of the Corps. Without any medicine, Lewis put his mother’s teachings to work. He directed his men to gather chokecherry, stripping the twigs and boiling them into a bitter liquid he then drank. Within a few hours, he noted in his journal, “I was entirely releived from pain and in fact every symptom of the disorder forsook me; my fever abated, a gentle perspiration was produced and I had a comfortable and refreshing nights rest.”

Many of Lewis’ letters to his mother survived, and they show he had a very close bond with her. He wrote to her frequently, and the letters between the two indicated they shared a sense of humor and wit. Lucy was devastated by the loss of her son. When Lewis died under mysterious circumstances in 1809, suicide was the prevailing theory. Lucy, however, refused to believe Lewis took his own life. She suspected foul play for the rest of her life. She continued to run her plantation and use her skills in herbal medicine until her own death in 1837. Her plantation burned to the ground in a fire shortly after her death. Many of her personal books and notes were lost in the blaze.

Marie Dorion

While Sacagawea may be the more well-known among the thousands of indigenous woman in Pacific Northwest history, she was not alone. Five years after her time with the Lewis and Clark Expedition, there would be another brave woman to contribute to westward exploration.

Marie Dorion was born in 1786 and was a member of the Ioway people. Like Sacagawea, she was married to a fur trader as a young teen. Her husband, Pierre Dorion Jr., was the son of a trapper and trader who also crossed paths with Lewis and Clark. When the Wilson Price Hunt expedition to Oregon set off in 1811 for John Jacob Astor, Marie and her husband joined them as interpreters. This expedition would result in the establishment of a fur-trading post in the Pacific Northwest: Fort Astoria.

Marie, Pierre, and their two young sons continued to live in the Pacific Northwest after Fort Astoria was founded. In 1814, tragedy struck. Pierre and a trapping party were attacked and killed in what is now present-day Idaho. Marie, learning of the impending attack, took her children and rode to her husband’s camp. She arrived too late, finding Pierre and most of the party dead. Only one trapper survived, but he succumbed to his injuries by nightfall despite Marie’s best efforts to save him.

Several horses had been left behind at the campsite. Marie took them and her children back to a small fur trading post. Upon returning, she discovered the staff of the trading post had been attacked and killed as well. She set off for another trading post, but both horses collapsed while traversing the Blue Mountains. There she stayed with her sons for fifty days, surviving through the fierce winter until she could continue westward. In the early spring, she reached a Walla Walla village who offered her support in her journey back to Fort Astoria.

Marie married twice more and had three more children, settling near St. Louis, Oregon. She lived there for the rest of her days, passing away in 1850. She was buried in the church in St. Louis, but the church burned to the ground in 1880 and record of her burial was lost until years later. In 2014, a service was held at the church and a marker installed to honor her legacy.