By Cathy Peterson, NPS Education Specialist

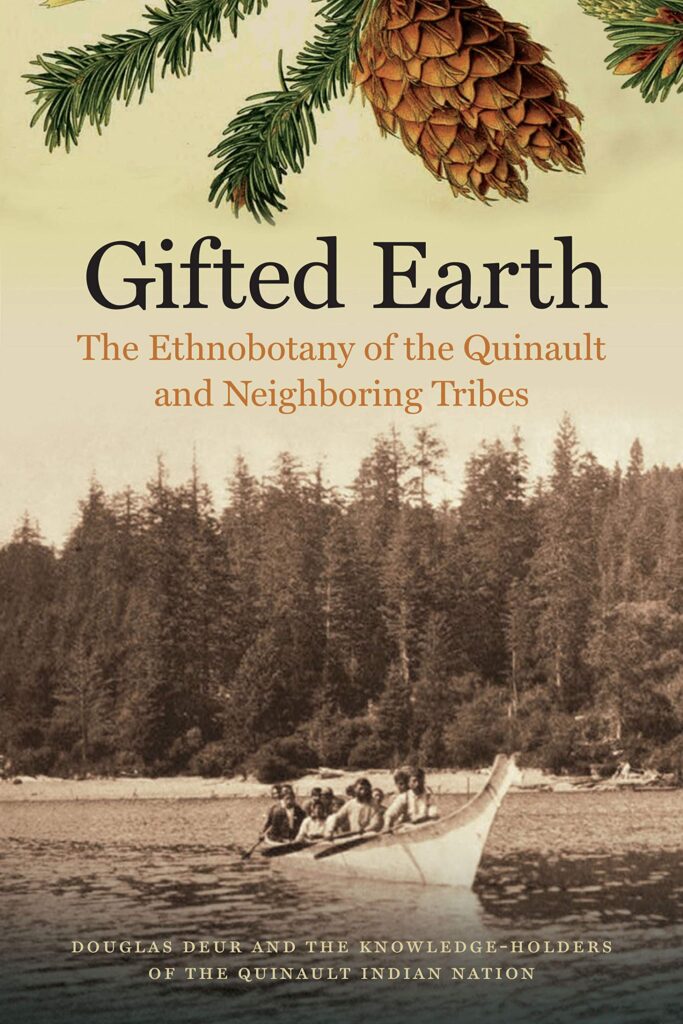

The Knowledge-Holders of the Quinault Indian Nation and author Doug Deur have given readers a beautiful and useful guide to regional ethnobotany. “Gifted Earth: The Ethnobotany of the Quinault and Neighboring Tribes” (Oregon State University Press and published in cooperation with the Quinault Indian Nation, 2022) is a gorgeous meditation on Indigenous plant knowledge and use as “living tradition.”

The book covers trees, shrubs, and other plants as food, medicine and materials. Descriptions of iconic trees and plants – Western redcedar to Sitka spruce, Indian tea to Oregon grape – are featured in its pages, as well as where to find them, when to gather, and traditional management and care practices. There is also cautionary information for harvest and consumption, as well as reminders not to forage without permission, and to avoid places where harvest isn’t allowed. That can include places in Quinault Country that are reserved as “cultural sites” and visited only by tribal members for plant gathering.

For the reader, “Gifted Earth” features many wild plants of interest that are known to Indigenous and non-Indigenous people on the Oregon and Washington coasts, and available for harvest in appropriate amounts and manners. Some of the plants, such as the native trailing blackberry, are ubiquitous North Coast summer favorites. The little purplish black jewels, born on low vines, appear in open woods and clearings, as well as along water and roadways. Another tasty treat, the thimbleberry, is making a late appearance this year after a wet spring. “Gifted Earth” reminds us the value also of the plant’s edible shoots, gathered primarily in spring.

Unique to the guide are recollections and references provided by Quinault people long familiar with the trees and plants. Generous commentaries on harvesting and eating, such as advisories on the best time to take salmonberries, or insight into the tradition of collecting Sitka spruce roots for weaving, or just appreciation for a great pie make “Gifted Earth” special. “My wife every year makes a couple of wild blackberry pies with the huckleberries mixed 50-50. The huckleberries are so sweet and the tartness of that wild blackberry – that’s just awesome,” shares Gerald Ellis.

Evocative descriptions make “Gifted Earth” less of a field guide, and more of an immersive companion. These anecdotes pepper the page margins and personalize the botanical information found within each short chapter.

“Gifted Earth” is also an instructive primer on traditional management and care strategies, such as using intentional fire as a way to remove dead and competing vegetation, and to open up space for desired plants. Intentional fire as a vegetation control method, a long-practiced Quinault and Indigenous tradition, has become a valuable tool to limit fire damage in the increasingly fire-prone western United States. Other traditional management strategies include selective pruning of canes and branches to produce more abundant fruits, as well as to yield building materials, such as straighter willow branches for weaving baskets and containers.

Deur acknowledges the dilemma of sharing cultural information that might cause traditional gathering spots to be overrun, or long-held practices to be abused. Yet, the “costs” of not sharing are also addressed – essential knowledge not getting passed down to younger tribal members, friends and allies; non-Native neighbors acting without knowledge of traditions, and potentially damaging harvest grounds and ecosystems. “Gifted Earth” draws on previous Quinault research and guidebooks created to preserve ethnobotanical knowledge for tribal members and natural resource managers who work for the Quinault Indian Nation. Sensitive cultural information from those guidebooks does not appear in “Gifted Earth,” such as the location of certain plant communities, yet “non-specialists” can benefit greatly from this collaborative volume in their own quest to understand and enjoy the region’s wild plants. “Done respectively,” Deur writes, “disclosure can help foster broad understanding and empathy, and buttress protections for many of the things tribes value most.”